"Goodbye kettle! You boiled well"

Many of us would feel strange saying a clear “Thank you!”, “Well done” or a meaningful “Goodbye!” to products. Yet in Advertising and Branding we often tug on these emotional strings at the on-boarding stage of the relationship. Brand agencies often talk about giving the brand a “personality” or “brand promise” Advertisers talk about “having a conversation between the customer and the provider”. Are these not equally emotional triggers created to tempt us to commit to a product purchase? Isn’t it equally strange to have a conversation at the beginning of a customer relationship, as it would be to have a conversation at the end?

The difference is in the mode of thinking at the beginning and the end of the relationship. The beginning - on-boarding stage of the relationship triggers our aspirations. Telling us we will be better with this purchase. What should be in place at the end of a customer relationship is self-reflection. But this is sadly overlooked because it stops our focus for purchasing new items.

Our life as a consumer is dominated by the noise driving us to purchase more, buy again, do more quicker, faster, easier. This drive has left our houses cluttered, our computers and our lives full of products we rarely use, and maybe don’t even need or like. We are trapped with these products because we can’t say goodbye. We don’t know how to because we have lost the capability to end relationships correctly - to have a good closure experience.

Where our ability to start a new consumer relationship (on-boarding) has been sharpened and crafted over generations by many industries focused on getting us to buy. In contrast, our ability at ending these relationships has few champions.

One person countering this is Marie Kondo, a self proclaimed declutterer from Japan, who has been helping hundreds clients declutter their homes. Although, according to Marie, there are many approaches to decluttering your home, and she has tried most, she believes that her's is the only approach that really works.

She believes, an area where many people fail is the approach to decluttering their home. Insisting that it cannot be done piecemeal. It has to be done with all items in each category at the same time. For example all clothes in the house, all books, etc. Any other approach fails as it becomes slow and looses its purpose.

The technique then requires people to reflect emotionally on each product. She asks the person to hold and feel each item. Handling them is vital, as it evokes important feelings and emotions about the item. Feeling for the item to ‘spark a feeling of joy’ If so, it should be kept and valued. If not the item should be ‘thanked and wished well for its future’ and disposed of appropriately.

What to throw away and what to keep is easier said then done. Many people find it difficult to say goodbye to products they have had for years. The product might mean something significant, but maybe not ‘joy’. This is a common blocker that Marie experiences daily and believes these emotions break down to 3 categories.

• an attachment to the past

• desire for stability in the future

• or a combination of both

People hold on to items out of fear of the future or attachment to the past. They are anxious to not lose that attachment to the past or that link with the future. With numerous clients that have gone through this she is confident that life with fewer objects is better and reassures many clients to be ruthless about what ‘brings them joy’ as a product.

The emotion that Marie brings to her technique is the most interesting. Instead of a cold hearted departure where the product ends it life in the waste bin, she insists that people say goodbye to the product they own, and wish it well.

Like wise she promotes a far more emotional relationship with all the products an individual keeps. Believing this increases a products life and gives greater value to ownership. This is nicely exampled in a passage from her book ‘The Life Changing Magic of Tidying’.

This is the routine I follow every day when I return from work first I lock the door and announce to my house “I’m home” picking up a pair of shoes I wore yesterday and left out in the hall I say “Thank you very much for your hard work” and put them away in the cupboard. I put my jacket and dress on a hanger and say “Good job!” I return to my bench and put my empty handbag in a bag and put it on the top shelf of the wardrobe saying “You did well have a good rest”.

Many of us would feel strange saying a clear “Thank you!”, “Well done” or a meaningful “Goodbye!” to products. Yet in Advertising and Branding we often tug on these emotional strings at the on-boarding stage of the relationship. Brand agencies often talk about giving the brand a “personality” or “brand promise” Advertisers talk about “having a conversation between the customer and the provider”. Are these not equally emotional triggers created to tempt us to commit to a product purchase? Isn’t it equally strange to have a conversation at the beginning of a customer relationship, as it would be to have a conversation at the end?

The difference is in the mode of thinking at the beginning and the end of the relationship. The beginning - on-boarding stage of the relationship triggers our aspirations. Telling us we will be better with this purchase. What should be in place at the end of a customer relationship is self-reflection. But this is sadly overlooked because it stops our focus for purchasing new items.

But this is where Marie Kondo, brings us something important for Closure Experiences and products. It is the opportunity for self-reflection on a products usage and its end.

The most many of us do when we dispose of a product is put it in the right recycling bin. This at most provides an emotionless thought about product materials, but it does nothing to provide emotional meaning to the end of a product relationship. And certainly doesn’t induce self-reflection.

To deal with something like climate change for consumers we are going to need better emotional persuasion than the dry and worthy arguments of Reduce, Recycle, Renew. We need to get emotional about endings and seize the opportunity for self-reflection. This would help us ask deeper questions about our personal consumption. And this would surely be the start of individual behaviour change.

So maybe saying goodbye to products is a good start. Try it next time you end a product relationship.

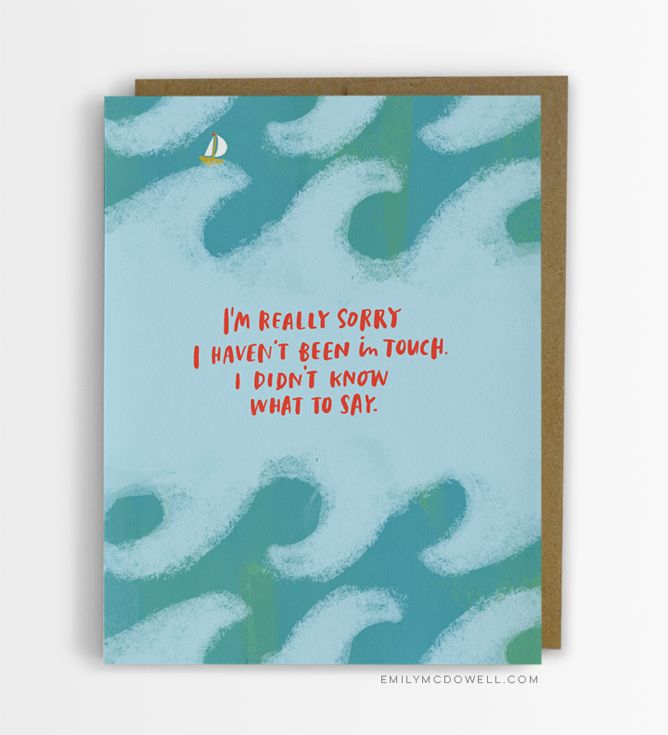

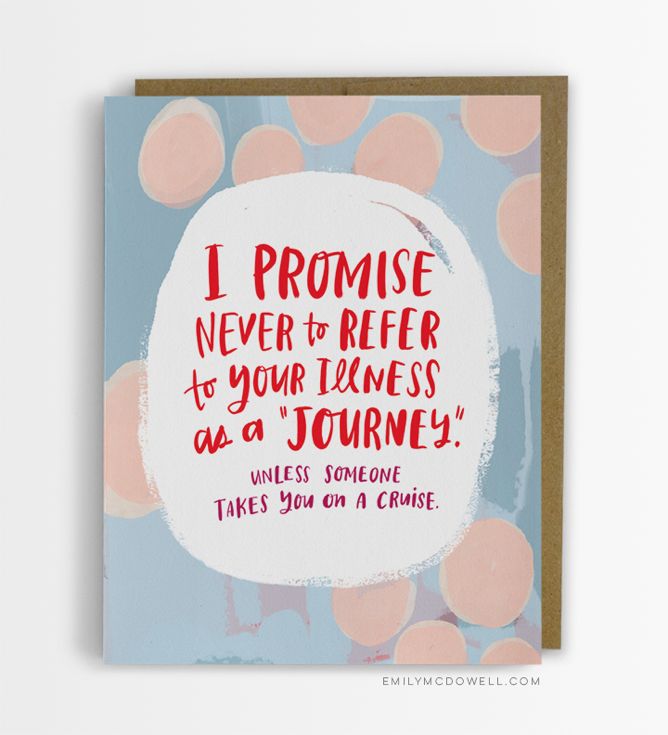

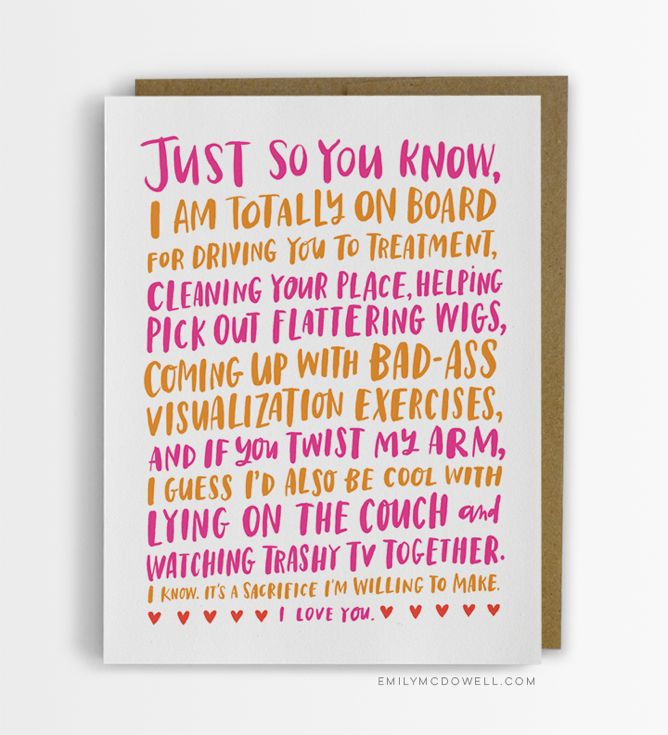

Empathy Cards

Emily’s Empathy Cards, bring a rare confidence and warmth to this situation. They are not the whimsical, or even meaningless ‘get well soon’ cards. But portray real feelings and some frustrations that are felt by the patient when dealing with close ones at this stage. They bridge the gap of not knowing what to say, when words are so hard to find. They are a great example of dealing with fatality of life.

A new set of cards designed by Emily McDowell brings home the difficulties people have in navigating emotions when someone has a fatal disease or is dying.

So many end of life experiences are lonely experiences for the dying person. As a recent cancer patient, Emily McDowell experienced these up close. Her frustrations were not with the progression of a disease like cancer or the resulting treatment and its side effects. Her frustrations lied with the behaviour of her close friends and family. Not that they done anything different to any other friends and family of this generation. They just didn’t know what to do or say. So sadly they said very little.

Courtesy of Emily McDowell

Generations ago, life was far more delicate. Death was common place. So our relationship with it was more familiar. People were comfortable to talk about it, and knew its path.

Today, we are distanced from it by many walls. The dying are often removed from their home, looked after by service personal, high on disease-fighting drugs. Those final moments lack the personal meaning they had in the past. And we subsequently lose the ability to deal with death when a loved one faces it. Sadly that often means that dying person faces death alone.

Courtesy of Emily McDowell

Courtesy of Emily McDowell

Emily’s Empathy Cards, bring a rare confidence and warmth to this situation. They are not the whimsical, or even meaningless ‘get well soon’ cards. But portray real feelings and some frustrations that are felt by the patient when dealing with close ones at this stage. They bridge the gap of not knowing what to say, when words are so hard to find. They are a great example of dealing with fatality of life and dealing with closure in sensitive way.

Courtesy of Emily McDowell

Courtesy of Emily McDowell

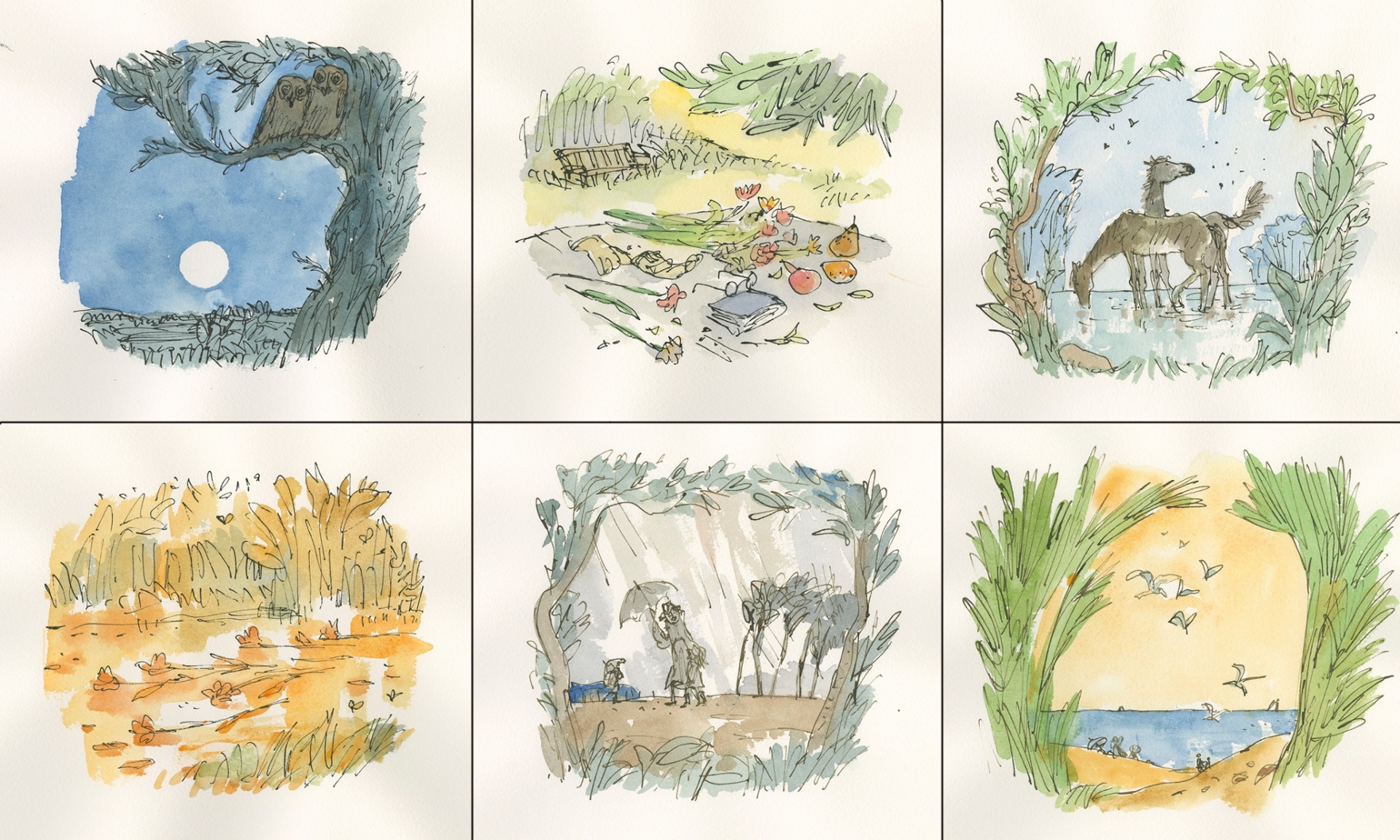

End of Life Room

A hospital is often a very frightening place for anyone, but particularly young people. The medicalisation of every issue often overlooks the issue of death. Instead the medical system applies its enormous arsenal to all situations. This arsenal lacks the poignance that is required when all that can be done, has been done.

The ‘End of Life Room’ at Great Ormond Street captures the need of reflection and grief well by decorating it with illustrations from Quentin Blake and removing a great deal of the technology and medical instruments common in hospitals. Well done Great Ormond Street and Jenny and Michael Walker who helped establish the room.

Its surprising how little we acknowledge the end of our life. We are certainly all going to experience this, so why do we fail so often at acknowledging it. This is even more acute when we consider hospitals. A place where 32% of us will experience our last days.

This issue covered again today, in an article by the Observer - Great Ormond Street Hospital have just established an ‘End of Life Room’. This room is dedicated to the terminally ill children who have exhausted procedures and interventions to live out their final days with their grieving family. The issue was highlighted by a family who wanted to stay with their terminally ill child in the final days of his life yet had no-where appropriate to do this at the hospital. After their child died they talked to the hospital about their idea of an ‘end of life room’ and raised £46,000 to establish the vision.

A hospital is often a very frightening place for anyone, but particularly young people. The medicalisation of every issue often overlooks the issue of death. Instead the medical system applies its enormous arsenal to all situations. This arsenal lacks the poignance that is required when all that can be done, has been done.

The ‘End of Life Room’ at Great Ormond Street captures the need of reflection and grief well by decorating it with illustrations from Quentin Blake and removing a great deal of the technology and medical instruments common in hospitals. Well done Great Ormond Street and Jenny and Michael Walker who helped establish the room.

The most distant endings

Such a tiny fraction of items on earth get to leave it. So it's refreshing that the ones who do, have a spectacular and well thought through ending.

Few products, services or digital services have there end designed, let alone in the detail that is required for any space program.

These versions of endings from @duncangeere at How We Get To Next are good inspiration for us all to think more about long term design or how to design endings.

Such a tiny fraction of items on earth get to leave it. So it's refreshing that the ones who do, have a spectacular and well thought through ending.

Few products, services or digital services have there end designed, let alone in the detail that is required for any space program.

These versions of endings from @duncangeere at How We Get To Next are good inspiration for us all to think more about long term design or how to design endings.

1. Leave It There

2. Shoot It Down

3. Into the Unknown

4. Crash Landing

3 ways to tell people they're dying

Telling people about the end of their life can be one of the most difficult things for medical staff to do. Surprisingly, these skills have only really been taught to medical students during the last couple of decades.

The 3 techniques provide interesting perspectives for designing the end of service or product relationships - setting the right environment, gauging what the user knows of the situation, providing lots of opportunity for questions - are just some examples of good practice in closure experiences.

Telling people about the end of their life can be one of the most difficult things for medical staff to do. Surprisingly, these skills have only really been taught to medical students during the last couple of decades. Previously medical students would rely on their own skills to navigate such situations, as Atul Gawande reflects on in his book Being Mortal.

“I learned about a lot of things in medical school, but mortality wasn’t one of them. Our textbooks had almost nothing on ageing or frailty or dying. How the process unfolds, how people experience the end of their lives, and how it affects those around them seemed beside the point. The way we saw it, and the way our professors saw it, the purpose of medical schooling was to teach how to save lives, not how to tend to their demise.”

Thankfully there is a far more empathetic approach now with a number of processes to support it. Many have an acronym (of course they would), coincidentally the ones I have included here all happen to be 6 step processes.

The most compelling I believe is the BREAKS version as I think it makes the most sense with the least effort and is therefore easier to remember for those using it.

All the techniques provide interesting perspectives for designing the end of service or product relationships - setting the right environment, gauging what the user knows of the situation, providing lots of opportunity for questions - are just some examples of good practice in closure experiences.

Below is a chart of the techniques in detail, and further links to their sources.

| Framework for Breaking Bad News | BREAKS | SPIKES |

|---|---|---|

| Based on a number of people’s work: Brod et al, 1986; Maguire and Faulkner, 1988; Sanson-Fisher, 1992, Buckman, 1994; Cushing and Jones 1995). From Silverman J., Kurtz S.M., Draper J. (1998) Skills for Communicating with Patients. Radcliffe Medical Press Oxford References | BREAKS’ Protocol for Breaking Bad News Vijayakumar Narayanan, Bibek Bista,1 and Cheriyan Koshy2 | SPIKES—A Six-Step Protocol for Delivering Bad News: Application to the Patient with Cancer Walter F. Bailea, Robert Buckmanb, Renato Lenzia, Gary Globera, Estela A. Bealea and Andrzej P. Kudelkab |

| http://www.skillscascade.com/badnews.htm | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3144432/ | http://theoncologist.alphamedpress.org/content/5/4/302.full |

| Preparation: · set up appointment as soon as possible · allow enough uninterrupted time; if seen in surgery, ensure no interruptions · use a comfortable, familiar environment · invite spouse, relative, friend, as appropriate · be adequately prepared re clinical situation, records, patient’s background · doctor to put aside own “baggage” and personal feelings wherever possible | Background An effective therapeutic communication is dependent on the in-depth knowledge of the patient’s problem. The accessibility of electronic media has given ample scope for obtaining enough data on any issue, though authenticity is questionable. It is highly desirable to prepare answers for all questions that can be anticipated from the patient. The physician must be aware of the patient/relative who comes after “googling” the problem. It may not be possible to answer all questions, but all reasonable doubts of the patient as well as his relatives should be cleared. If the physician has not done his homework meticulously, the session should be postponed. Apart from doing an in-depth study on the patient’s disease status, his emotional status, coping skills, educational level, and support system available are also reviewed before attempting to break the bad news. Cultural and ethnic background of the patient is also very important. The physician has to be sensitive to the cultural orientation of the patient, and it should be respected. The individual’s thinking and actions are governed by his cultural orientation. The physical set up is very important in accomplishing this difficult task. The mobile phone must be switched off. All physical barriers must be removed to maintain eye contact. A co-worker’s help for transcribing the conversation is helpful. Emotional breakdown can be expected; hence, the physician may have to console the patient as well. Regressive behaviors need to be tackled with a complimentary transaction. The appointment length should be sufficient to complete the task | STEP 1: S—SETTING UP the Interview Mental rehearsal is a useful way for preparing for stressful tasks. This can be accomplished by reviewing the plan for telling the patient and how one will respond to patients' emotional reactions or difficult questions. As the messenger of bad news, one should expect to have negative feelings and to feel frustration or responsibility [55]. It is helpful to be reminded that, although bad news may be very sad for the patients, the information may be important in allowing them to plan for the future. Sometimes the physical setting causes interviews about sensitive topics to flounder. Unless there is a semblance of privacy and the setting is conducive to undistracted and focused discussion, the goals of the interview may not be met. Some helpful guidelines: Arrange for some privacy. An interview room is ideal, but, if one is not available, draw the curtains around the patient's bed. Have tissues ready in case the patient becomes upset. Involve significant others. Most patients want to have someone else with them but this should be the patient's choice. When there are many family members, ask the patient to choose one or two family representatives. Sit down. Sitting down relaxes the patient and is also a sign that you will not rush. When you sit, try not to have barriers between you and the patient. If you have recently examined the patient, allow them to dress before the discussion. Make connection with the patient. Maintaining eye contact may be uncomfortable but it is an important way of establishing rapport. Touching the patient on the arm or holding a hand (if the patient is comfortable with this) is another way to accomplish this. Manage time constraints and interruptions. Inform the patient of any time constraints you may have or interruptions you expect. Set your pager on silent or ask a colleague to respond to your pages |

| Beginning the session / setting the scene · summarise where things have got to date, check with the patient · discover what has happened since last seen · calibrate how the patient is thinking/feeling · negotiate agenda | Rapport Building rapport is fundamental to continuous professional relationship. The physician should establish a good rapport with the patient. He needs to have an unconditional positive regard, but has to stay away from the temptation of developing a patronizing attitude. The ease with which the rapport is being built is the key to continue conversation. A hostile attitude has disastrous outcome, so is a hurried manner. It is necessary to provide ample space for the windows of self-disclosure to open up. The patient should be placed in a comfortable position. Present condition of the patient can be enquired through open questions. If the patient is not prepared for the bad news, especially after getting his /her symptoms well palliated, let him finish the reports of well being, and then try to take cues from his conversation to initiate the process of breaking bad news | STEP 2: P—Assessing the Patient's PERCEPTION Steps 2 and 3 of SPIKES are points in the interview where you implement the axiom “before you tell, ask.” That is, before discussing the medical findings, the clinician uses open-ended questions to create a reasonably accurate picture of how the patient perceives the medical situation—what it is and whether it is serious or not. For example, “What have you been told about your medical situation so far?” or “What is your understanding of the reasons we did the MRI?”. Based on this information you can correct misinformation and tailor the bad news to what the patient understands. It can also accomplish the important task of determining if the patient is engaging in any variation of illness denial: wishful thinking, omission of essential but unfavorable medical details of the illness, or unrealistic expectations of treatment [56]. |

| Sharing the information · assess the patient’s understanding first: what the patient already knows, is thinking or has been told · gauge how much the patient wishes to know [1] · give warning first that difficult information coming e.g. "I'm afraid we have some work to do...." "I'm afraid it looks more serious than we had hoped...." · give basic information, simply and honestly; repeat important points · relate your explanation to the patient’s framework · do not give too much information too early; don’t pussyfoot but do not overwhelm · give information in small “chunks”; categorise information giving · watch the pace, check repeatedly for understanding and feelings as you proceed · use language carefully with regard given to the patient's intelligence, reactions, emotions: avoid jargon | Exploring Whenever attempting to break the bad news, it is easier for the physician to start from what the patient knows about his/her illness. Most of the patients will be aware of the seriousness of the condition, and some may even know their diagnosis. The physician is then in a position of confirming bad news rather than breaking it. The history, the investigations, the difficulties met in the process etc need to be explored. What he/she thinks about the disease and even the diagnosis itself can be explored, and the potential conflicts between the patient’s beliefs and possible diagnosis can be identified. The dynamics of the family and the coping reservoir of the patient are very important in delivering the bad news. Try to involve the significant other people of the patient in the decision-making process, if allowed by the patient. At least few patients may respond in a bizarre way to the bad news. Hence, a careful exploration of all these points should be carried out. A common tendency from the physicians is that they jump into premature re assurances. Premature reassurance occurs when a physician responds to a patient concern with reassurance before exploring and understanding the concerns.[25] Absolute certainties about longevity cannot be given to a patient. The prognosis can be explained in detail; with all available data. A reasonable conclusion based on the facts can be presented | STEP 3: I—Obtaining the Patient's INVITATION While a majority of patients express a desire for full information about their diagnosis, prognosis, and details of their illness, some patients do not. When a clinician hears a patient express explicitly a desire for information, it may lessen the anxiety associated with divulging the bad news [57]. However, shunning information is a valid psychological coping mechanism [58, 59] and may be more likely to be manifested as the illness becomes more severe [60]. Discussing information disclosure at the time of ordering tests can cue the physician to plan the next discussion with the patient. Examples of questions asked the patient would be, “How would you like me to give the information about the test results? Would you like me to give you all the information or sketch out the results and spend more time discussing the treatment plan?”. If patients do not want to know details, offer to answer any questions they may have in the future or to talk to a relative or friend |

| Being sensitive to the patient · read the non-verbal clues; face/body language, silences, tears · allow for “shut down” (when patient turns off and stops listening) and then give time and space: allow possible denial · keep pausing to give patient opportunity to ask questions · gauge patient’s need for further information as you go and give more information as requested, i.e. listen to the patient's wishes as patients vary greatly in their needs · encourage expression of feelings, give early permission for them to be expressed: i.e. “how does that news leave you feeling”, “I’m sorry that was difficult for you”, “you seem upset by that” · respond to patients feelings and predicament with acceptance, empathy and concern · check patient’s previous knowledge about information given · specifically elicit all the patient’s concerns · check understanding of information given ("would you like to run through what are you going to tell your wife?") · be aware of unshared meanings (i.e. what cancer means for the patient compared with what it means for the physician) · do not be afraid to show emotion or distress | Announce A warning shot is desirable, so that the news will not explode like a bomb. Euphemisms are welcome, but they should not create confusion. The patient has the right to know the diagnosis, at the same time he has the right to refrain from knowing it. Hence, announcement of diagnosis has to be made after getting consent. The body language of both the physician and patient is very important, and the physician is supposedly a mirror image of the patient. The embarrassment, agony, and fear of the patient should be reflected in the physician (mirroring the emotions), so that the patient will identify the physician as one close to himself. Announcement of the bad news must be in straightforward terms, avoiding the medical jargon completely. Lengthy monolog, elaborate explanations, and stories of patients who had similar plight are not desirable. Information should be given in short, easily comprehensible sentences. A useful rule of thumb is not to give more than three pieces of information at a time.[26 | STEP 4: K—Giving KNOWLEDGE and Information to the Patient Warning the patient that bad news is coming may lessen the shock that can follow the disclosure of bad news [32] and may facilitate information processing. Examples of phrases that can be used include, “Unfortunately I've got some bad news to tell you” or “I'm sorry to tell you that…”. Giving medical facts, the one-way part of the physician-patient dialogue, may be improved by a few simple guidelines. First, start at the level of comprehension and vocabulary of the patient. Second, try to use nontechnical words such as “spread” instead of “metastasized” and “sample of tissue” instead of “biopsy.” Third, avoid excessive bluntness (e.g., “You have very bad cancer and unless you get treatment immediately you are going to die.”) as it is likely to leave the patient isolated and later angry, with a tendency to blame the messenger of the bad news. Fourth, give information in small chunks and check periodically as to the patient's understanding. Fifth, when the prognosis is poor, avoid using phrases such as “There is nothing more we can do for you.” This attitude is inconsistent with the fact that patients often have other important therapeutic goals such as good pain control and symptom relief. |

| Planning and support · having identified all the patient’s specific concerns, offer specific help by breaking down overwhelming feelings into manageable concerns, prioritising and distinguishing the fixable from the unfixable · identify a plan for what is to happen next · give a broad time frame for what may lie ahead · give hope tempered with realism (“preparing for the worst and hoping for the best”) · ally yourself with the patient (“we can work on this together ...between us”) i.e. co-partnership with the patient / advocate of the patient · emphasise the quality of life · safety net | Kindling People listen to their diagnosis differently. They may break down in tears. Some may remain completely silent, some of them try to get up and pace round the room. Sometimes the response will be a denial of reality, as it protects the ego from a potential shatter. A gallows humor is also an expected behavior. These are all predictable responses. Adequate space for the free flow of emotions has to be given. Most of the time, patients will not actively listen to what the physician say after the pronouncement of the status. An overwhelming feeling of a grim fate can ignore further explanations and narratives from the physician’s part. Hence, it is advisable to ensure that the patient listens to what is being told, by asking them questions like “are you there?”, “do you listen to me?” etc. It involves asking the patient to recount what they have understood. Be clear that the patient did not misunderstand the nature of disease, the gravity of situation, or the realistic course of disease with or without treatment options. While trying to kindle the emotions, care has to be taken not to utter any unrealistic treatment options. The patient and their relatives will cling on to it, and subsequently feel embarrassed because of its unrealistic nature. Answers have to be tailored to the question, and physician should stay away from lecturing to the patient. Lecturing occurs when a physician delivers a large chunk of information without giving the patient a chance to respond or ask questions.[27] Beware of the “differential listening,” as the patient will listen to only those information he/she wants to hear. Dealing with denial is another difficult task. It may be necessary to challenge denial because the patient may have some important unfinished business to conduct, or because the patient is refusing treatment that might alleviate symptoms. In such situations, attempts to break the defense without mutilating the ego should be attempted | STEP 5: E—Addressing the Patient's EMOTIONS with Empathic Responses Responding to the patient's emotions is one of the most difficult challenges of breaking bad news [3, 13]. Patients' emotional reactions may vary from silence to disbelief, crying, denial, or anger. When patients get bad news their emotional reaction is often an expression of shock, isolation, and grief. In this situation the physician can offer support and solidarity to the patient by making an empathic response. An empathic response consists of four steps [3]: First, observe for any emotion on the part of the patient. This may be tearfulness, a look of sadness, silence, or shock. Second, identify the emotion experienced by the patient by naming it to oneself. If a patient appears sad but is silent, use open questions to query the patient as to what they are thinking or feeling. Third, identify the reason for the emotion. This is usually connected to the bad news. However, if you are not sure, again, ask the patient. Fourth, after you have given the patient a brief period of time to express his or her feelings, let the patient know that you have connected the emotion with the reason for the emotion by making a connecting statement. An example: Doctor: I'm sorry to say that the x-ray shows that the chemotherapy doesn't seem to be working [pause]. Unfortunately, the tumor has grown somewhat. Patient: I've been afraid of this! [Cries] Doctor: [Moves his chair closer, offers the patient a tissue, and pauses.] I know that this isn't what you wanted to hear. I wish the news were better. In the above dialogue, the physician observed the patient crying and realized that the patient was tearful because of the bad news. He moved closer to the patient. At this point he might have also touched the patient's arm or hand if they were both comfortable and paused a moment to allow her to get her composure. He let the patient know that he understood why she was upset by making a statement that reflected his understanding. Other examples of empathic responses can be seen in Table 2⇓. View this table: In this window In a new window Table 2. Examples of empathic, exploratory, and validating responses Until an emotion is cleared, it will be difficult to go on to discuss other issues. If the emotion does not diminish shortly, it is helpful to continue to make empathic responses until the patient becomes calm. Clinicians can also use empathic responses to acknowledge their own sadness or other emotions (“I also wish the news were better”). It can be a show of support to follow the empathic response with a validating statement, which lets the patient know that their feelings are legitimate (Table 3⇓). View this table: In this window In a new window Table 3. Changes in confidence levels among participants in workshops on communicating bad news Again, when emotions are not clearly expressed, such as when the patient is silent, the physician should ask an exploratory question before he makes an empathic response. When emotions are subtle or indirectly expressed or disguised as in thinly veiled disappointment or anger (“I guess this means I'll have to suffer through chemotherapy again”) you can still use an empathic response (“I can see that this is upsetting news for you”). Patients regard their oncologist as one of their most important sources of psychological support [63], and combining empathic, exploratory, and validating statements is one of the most powerful ways of providing that support [64-66] (Table 2⇑). It reduces the patient's isolation, expresses solidarity, and validates the patient's feelings or thoughts as normal and to be expected. |

| Follow up and closing · summarise and check with patient · don't rush the patient to treatment · set up early further appointment, offer telephone calls etc. · identify support systems; involve relatives and friends · offer to see/tell spouse or others · make written materials available | Summarize The physician has to summarize the session and the concerns expressed by the patient during the session. It essentially highlights the main points of their transaction. Treatment/care plans for the future has to be put in nutshell. The necessary adjustments that have to be made both emotionally and practically need to be stressed. A written summary is appreciable, as the patients usually take in very little when they are anxious. Offering availability round the clock and encouraging the patient to call for any reasons are very helpful. An optimistic outlook has to be maintained, and volunteer if asked by the patient for disseminating the information to the relatives. The review date also has to be fixed before concluding the session. At the end of the session, make sure that the patient’s safety is ensured once they leave the room. He/she should not be permitted to drive back home all alone, and find whether someone at home can provide support. Patient may even try to commit suicide if he/she feels extremely desperate. Patient should be assured that the physician will be actively participating in all ongoing care plans. | STEP 6: S—STRATEGY and SUMMARY Patients who have a clear plan for the future are less likely to feel anxious and uncertain. Before discussing a treatment plan, it is important to ask patients if they are ready at that time for such a discussion. Presenting treatment options to patients when they are available is not only a legal mandate in some cases [68], but it will establish the perception that the physician regards their wishes as important. Sharing responsibility for decision-making with the patient may also reduce any sense of failure on the part of the physician when treatment is not successful. Checking the patient's misunderstanding of the discussion can prevent the documented tendency of patients to overestimate the efficacy or misunderstand the purpose of treatment [7-9, 57]. Clinicians are often very uncomfortable when they must discuss prognosis and treatment options with the patient, if the information is unfavorable. Based on our own observations and those of others [1, 5, 6, 10, 44-46], we believe that the discomfort is based on a number of concerns that physicians experience. These include uncertainty about the patient's expectations, fear of destroying the patient's hope, fear of their own inadequacy in the face of uncontrollable disease, not feeling prepared to manage the patient's anticipated emotional reactions, and sometimes embarrassment at having previously painted too optimistic a picture for the patient. These difficult discussions can be greatly facilitated by using several strategies. First, many patients already have some idea of the seriousness of their illness and of the limitations of treatment but are afraid to bring it up or ask about outcomes. Exploring the patient's knowledge, expectations, and hopes (step 2 of SPIKES) will allow the physician to understand where the patient is and to start the discussion from that point. When patients have unrealistic expectations (e.g., “They told me that you work miracles.”), asking the patient to describe the history of the illness will usually reveal fears, concerns, and emotions that lie behind the expectation. Patients may see cure as a global solution to several different problems that are significant for them. These may include loss of a job, inability to care for the family, pain and suffering, hardship on others, or impaired mobility. Expressing these fears and concerns will often allow the patient to acknowledge the seriousness of their condition. If patients become emotionally upset in discussing their concerns, it would be appropriate to use the strategies outlined in step 5 of SPIKES. Second, understanding the important specific goals that many patients have, such as symptom control, and making sure that they receive the best possible treatment and continuity of care will allow the physician to frame hope in terms of what it is possible to accomplish. This can be very reassuring to patients. |

Header image courtesy of Alex Proimos

Charting death

Three versions of death by Atul Gawande in his excellent and insightful book Being Mortal.

Three versions of death by Atul Gawande in his excellent and insightful book Being Mortal.

The first one considers historically how we would experience death. It plots the expected life, and death experience of a person. With life being such a sensitive gift. As he puts it “your life would putter along nicely, not a problem in the world. Then illness would strike and the bottom would drop out like a trap door”.

Old death wasn't a surprise

The second illiterates more recent experience of death with the introduction of drugs that can cure and halt deaths march. “Our treatments can stretch the decent out until it ends up looking less like a cliff and more like a hilly road down the mountain.”

Recent death was a bumpy ride

The third illustrates the current western scenario that medicalises the progress of death to such a degree that we can’t really tell when meaningful life has ended. We can be kept alive almost indefinitely on with a variety of machines and medicines. “We reduce the blood pressure here, beat back the osteoporosis there, control this disease, track that one, replace the failed joint, valve, piston, watch the central processing unit gradually give out. The curve of life becomes a long, slow fade.”

Current death is medicalised

512,000 desperate customers seeking conclusion

In the last few years, complaints to the UK Financial Ombudsman have increased fourfold. In 2009 they considered 127,000 cases, and in 2014 this leapt to 512,000. It’s saddening to think that we have so many un-resolved issues between consumers and the financial services industry. The sales culture they have bred emphasises the on-boarding of users over the closure experience of a service – the ultimate delivery of the service.

The Financial Ombudsman service was established by the UK Parliament to resolve issues between financial companies and consumers. It’s a free service that aims to negotiate a settlement between parties. Although they don’t have any legal powers to enforce fines, they do apply the rules of the regulator who has the powers to. The cases cover a broad range of financial issues, from pawnbroking to pensions and bonds to banking. One of the biggest issues in recent times is the mis-selling of payment protection insurance (PPI).

In the last few years, complaints to the UK Financial Ombudsman have increased fourfold. In 2009 they considered 127,000 cases, and in 2014 this leapt to 512,000. It’s saddening to think that we have so many un-resolved issues between consumers and the financial services industry. The sales culture they have bred emphasises the on-boarding of users over the closure experience of a service – the ultimate delivery of the service. This is surfaced when the customer becomes unsatisfied with the service delivery and calls the Financial Ombudsman to resolve the issue. The closure experience for these customers should have given the peace of mind that many financial products promise in the advert, but a common experience is that the T&Cs dictate otherwise.

According to the Financial Ombudsman, many of the complaints they receive arise through misunderstanding and are quickly resolved through ‘clear explanation of what has happened and why’. This highlights the issue with T&Cs and their impenetrable nature. T&Cs are the clearest and most factual version of a closure experiences the provider can imagine. Sadly, it is written in such a way as to make it totally alien to the customer. We see this in how ridiculously un-user centric they are, by their length and by their complexity.

Fairer Finance found that only 27 per cent of people read the T&Cs of financial services products (2,000 surveyed). Of those who read them, only 17% understood them. They also found that the length of the documents put many people off, which isn’t surprising given that HSBC, the worst offender in banking comes in at 34,000 words, 5,000 longer than John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men. The worst for the insurance industry is Endsleigh’s at 37,676 – longer than Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad.

With 512,000 disputes outstanding with the Financial Ombudsman we can see the customer is stranded between a compelling advert and sales-based culture on one hand, and the impenetrable T&Cs and poorly thought through closure experience on the other. A fresh user-centric approach, focusing on Closure Experiences that fulfil delivery of a service’s promise is what we should be aiming for. In turn, we’d be reducing the Financial Ombudsman’s workload to something less embarrassing for a world-leading service industry.

Questionnaire about Closure

I am aiming to get some tangible data about closure experiences at work and as consumers. I would really appreciate a few minutes of your time to do this short questionnaire.

Talking about Closure at Glug

I was flattered to be asked to speak at Glug recently. Its a great event, hosted in a nightclub in Shoreditch, London, with a smart savvy crowd from the digital/start-up community. Below is the SlideShare of the deck I showed at the event:

I was flattered to be asked to speak at Glug recently. Its a great event, hosted in a nightclub in Shoreditch, London, with a smart savvy crowd from the digital/start-up community. Below is the SlideShare of the deck I showed at the event:

image courtesy of @jazzpazz

Waste in the digital landscape

The simplest type of waste is the visible kind. It is easy to identify rubbish on the streets, or fly tipping on a country road, but as we engage in progressively more complex systems - mechanical, chemical, digital, we experience increasingly more complex forms of waste that are harder to identify.

simplest type of waste is the visible kind

Visible waste

The simplest type of waste is the visible kind. It is easy to identify rubbish on the streets, or fly tipping on a country road, but as we engage in progressively more complex systems - mechanical, chemical, digital, we experience increasingly more complex forms of waste that are harder to identify.

Much of the early types of waste from manufacturing were clearly visible - the massive slag heaps of the coal industry or the bellowing smoke from a factory's chimney stack. The evidence of waste was there for everyone to see. In Britain this resulted in the first environmental law - the Alkali Acts, passed in 1863 to limit the pollution given off by the production of soda ash.

Biological waste

100 years after the first waste laws were introduced the emerging chemical industry was brought into the spotlight when Rachel Carson's Silent Spring was published. She highlighted the damage we were unknowingly doing to the ecosystem by the use of pesticides. This invisible damage was particularly exampled by one pesticide - DDT - which was being successfully used on farms to kill off a range of pests but had an enormous knock-on effects on the food chain; killing off birds, wildlife and even humans in a couple of instances.

Digital Waste

The increased use of digital products highlights a new era for waste. Not only the complex components used in the production of TV, computers and phones that then need expert dismantling in order to be recycled, but the digital services that create complex cultural waste that we don’t yet fully understand.

We can categories digital waste into 3 groups.

‘Bit Rot’ - out-dated computer applications and their offspring files.

Forgotten digital services that retain your user ID

Unwanted evidence of ourselves online (photos, videos, etc)

Bit Rot

Vint Cerf, who is the Vice President at Google and is considered to be one of the founding fathers of the internet, coined the phrase 'Bit Rot' to describe the redundancy of digital content that requires a reader application. If that content is not updated regularly, its reader application becomes obsolete and the content unreadable. If you think of all of the digital format presentations you have done in the last 15 years and how many would still be usable then you start to get an idea of the loss of knowledge we are experiencing - think Alexandra Library of the modern world.

Forgotten Digital Services

This year there are 1.4 billion smartphone users on earth. Assuming that each one of these will be signed up to some kind of digital service - which many of the manufactures insist on at some level - that’s a lot of digital service relationships getting started. WIth the average life of a smartphone lasting around 2 years that service might be active for only a couple of years.

We rarely close the digital relationships we start. We might stop using them but these unclosed services will still be present on databases, returning results to search engines and although many users will be unaware of this, the identity they created will still be active.

Unwanted Evidence Online

Professor Mayer-Schönberger, in his book Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital Age (Princeton, 2009), highlights the problems of the accessibility to so much from our past and the potential damage caused by a compromising Facebook picture or some outdated information taken as fact. The context of these artefacts are vital to understanding them. This includes the context of time. Much of the content we keep online, will remain there long after the office party and long after you leave that job.

With each new industrial movement we have to look harder for the wasteful consequences. The intentions of factories in the industrial revolution was not to create smoke and smog, it was to manufacture products on a mass scale. It took the death of hundreds of people to highlight the need for the clean air act. The chemical industries of the 50s and 60s did not intend to kill off the entire food chain with DDT. Their intention was to aid farming production by reducing common pests. It took observations of the wider food chain to notice the real impact.

Worrying digital narcissism

New industries are often blinded by the benefits of the any new technology. The digital industry is no different. But unlike the industries of the past, the impact of digital waste won’t be a physical one, it will be a social and physiological one.

The emerging physiological tics we develop from using social media, the low level anxieties from fear of missing out, subconscious comparisons with “friends” or the embarrassment of being tagged in someone else's photo are all examples of the impact of this surfacing digital waste.

We need to sober up from the endless benefits of digital technology and start assessing its wasteful consequences. We need to evolve our understanding of digital waste, develop a vocabulary to acknowledge it and techniques to counter its long term effects.

6 reasons to end a relationship

With the first week of the year being one of the busiest for divorce lawyers its a good time to reflect on reasons why people end their marriages and what we can learn for designing closure experiences.

Listed below are 6 reasons people end their relationships according to Daphne Rose Kingma a relationship councillor. Lots of parallels for us to consider in the breakdown of service relationships or creating closure experiences.

With the first week of the year being one of the busiest for divorce lawyers its a good time to reflect on reasons why people end their marriages and what we can learn for designing closure experiences.

Listed below are 6 reasons people end their relationships according to Daphne Rose Kingma a relationship councillor. Lots of parallels for us to consider in the breakdown of service relationships or creating closure experiences.

Reasons to End it

1. Fights

One of the indicators of a relationship in trouble is that it has become a battleground. “All we do is fight; we can’t have a single normal conversation” Whenever a relationship gets to this point, it usually means that the life-giving, nourishing elements of the relationship have been depleted and it has moved into a degenerative phase.

2. Irreconcilable Differences

A couple is experiencing irreconcilable differences when either one of them finds that the area of common ground they once shared is now so small that what occupies that territory is a multitude of differences. Irreconcilable differences occur in certain strategic areas.

• A common one is time—how much time each partner wants to commit to the intimate life of the relationship.

• Often conflicts have to do with money. When his wife received her sizable inheritance, one man felt suddenly totally inadequate.

3. Boredom

One of the other ways you can tell it’s ending is that one day you may get up feeling depressed, vaguely disconnected and blue. Nothing terrible has happened, but I just have this creepy listless hopeless feeling.”

When you feel this way, it could be that the essential vitality in your relationship is gone. The thrill is gone; the zing has gone; there’s nothing happening between you two. You’re not “in love” anymore, and you’re also not having enough ongoing transactions that have meaning or provide

4. Emotional Distance

For most people, boredom is the most pervasive feeling that indicates a relationship is on its way out. But sometimes the feeling is much more acute. You become aware that this other person, to whom you’ve been relating, is no longer there when you reach out to make contact. You try to have a conversion and get no response, or you try to have a conversation and get a consistently negative response.

5. Changes In Venue

A lot of relationships, which have already outlived their usefulness really flounder and collapse when there is a change in the geographic circumstance of the relationship. Since we generally carry on our relationships in a daily and domestic fashion, there is much about a relationship that is supported by and contained within its specific geographical and domestic circumstances. A change in location or circumstance can bring out the fact that all the essential underpinnings in the relationship are already gone, that in a sense the relationship was being held together by the house, the neighbourhood, or the town.

6. Affairs

In general, we have agreed that sexual bonding is one of the ways we define our primary relationships. For this reason, it generally does have a divisive and corrosive effect when we dilute our commitment by having sex outside of our primary relationship. For when we do that, we take away one of the things which makes it unique and exclusive. This can’t help but affect the primary relationship. We all know this on an unconscious level, and that’s one of the reasons why, when we are trying to end a relationship but don’t know how, we often engage in an affair so that the affair can communicate our real intentions—intentions which are still unfocused or which we are afraid to communicate in a more direct way.

Endings Aligned

We have created a poster showing the variety of customer experience processes and how each of them end. From the marketing guru Philip Kotler to Colin Shaw and John Ivens' Great Customer Experiences, and Ron Zemke's Service Recovery. Contrasting these we show Daphne Rose Kingma's stages of people's love lives falling apart. Together they show opportunity areas for closure experiences to be created for customers.

We have created a poster showing the variety of customer experience processes and how each of them end. From the marketing guru Philip Kotler to Colin Shaw and John Ivens' Great Customer Experiences, and Ron Zemke's Service Recovery. Contrasting these we show Daphne Rose Kingma's stages of people's love lives falling apart. Together they show opportunity areas for closure experiences to be created for customers.

Endings Aligned poster Download here